What they didn’t tell you about the Indigenous origins of nonviolent resistance will fundamentally change how you understand protest and social justice.

With protests erupting around the US in light of the unprecedented militrization of domestic order, and in response to extrajudicial kidnappings, this conflict replays itself as a philosophical question of what type of response to oppression is acceptable. Protests are supposed to be nonviolent to retain their legitimacy. But what does that mean? Must protestors avoid conflict? Are they not justified in defending themselves?

These questions are ancient.

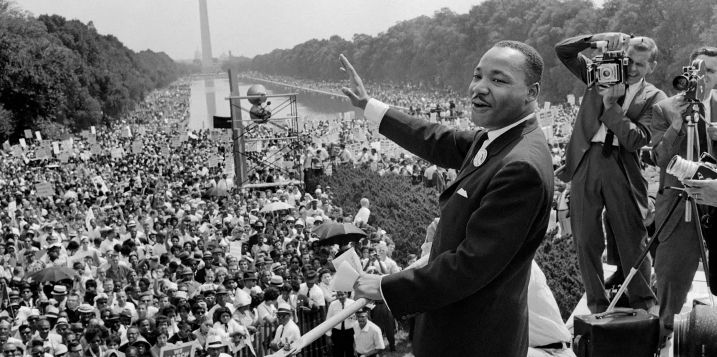

When we think about nonviolent resistance, most of us in the West immediately picture Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement. And rightly so—King’s leadership was transformative. But there’s a deeper story here, one that connects ancient Indigenous, and colonially erased, moral philosophy to modern social justice in ways that answers these ancient questions and provides moral clarity for the present moment.

The Gandhi Connection

Martin Luther King Jr. was explicit about his debt to Mahatma Gandhi, crediting him with showing that nonviolence could be “a powerful and effective social force on a large scale.” As King wrote in his essay “My Pilgrimage to Nonviolence”:

“Gandhi was probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force… It was in this Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking.”

~~King, M. L., Jr. (September 1, 1958). My Pilgrimage to Nonviolence. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.

This shortened version of chapter six of Stride Toward Freedom appeared in the September issue of Fellowship. In it, King traces the philosophical and theological underpinnings of his commitment to nonviolence, stating that “Gandhi was probably the first person in history to let the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force on a large scale.” King affirms his conviction that nonviolent resistance is “one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their quest for social justice.”

King saw Gandhi’s approach as Jesus’s “love ethic” applied to political action. But here’s where the story gets deeper and Indigenous.

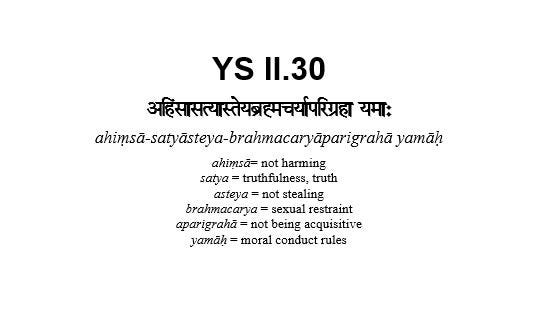

The Ancient Roots: Ahiṃsā and the Yoga Sūtra

Ahiṃsā literally translates to “non-harm,” but its meaning in practice is far more nuanced and radical than simple pacifism. This raises a crucial question that has puzzled philosophers and activists for millennia: if you’re committed to non-harm, does that mean you can’t defend yourself? Can’t act against injustice, even when that action involves risk or conflict?

Two Approaches to Nonviolence

In ancient Indian philosophy, there were two distinct ways of understanding nonviolence, and the difference between them is crucial for understanding modern social justice movements.

The first approach is teleological—focused purely on outcomes. This theory says: don’t break things, avoid activity that might lead to violence, stay passive. This is the nonviolence of withdrawal, of stepping back from conflict entirely. This is an entailment of Jainism’s basic moral philosophy. One can also here it in calls that protests remain simply “be peaceful” without challenging systems of oppression.

The second approach is procedural—focused on disrupting patterns of harm. This theory recognizes that sometimes, dismantling oppressive systems requires active confrontation. Under this understanding, even engaging in warfare could be consistent with ahiṁsā if it serves to protect the vulnerable and dismantle systems of oppression. This was the Yoga approach, famously explored in the Bhagavad Gītā, where Kṛṣṇa, on a battlefield prior to a war, motivates Arjuna to fight by way of arguments from Yoga.

(For more, see: Shyam Ranganathan (2024). White Supremacy and Two Theories of Ahiṁsā: Jainism vs. Yoga. Ahiṃsā in the Indic Traditions: Explorations and Reflections. J. D. Long and S. J. Rosen, Lexington: 123-144.)

The Universal Imperative to Activism

This procedural ahiṃsā operates on five key principles:

- Disrupt systemic harm wherever it occurs

- Participate in the facts, consisting in

- People not being deprived of what they require,

- Personal boundaries respected,

- Resulting in no appropriation and colonization

What This Means for Modern Social Justice

Nonviolence ≠ Passivism. True ahiṃsā is active, strategic, and disruptive. It works precisely because it dismantles oppression rather than simply avoiding conflict.

Nonviolence ≠ Martyrdom. The practitioner of ahiṃsā works to protect common space for everyone, including themselves. This isn’t about suffering for suffering’s sake—it’s about creating conditions where everyone can thrive.

Nonviolence = Revolutionary Action. When we understand nonviolence as a strategy for dismantling harmful systems rather than simply avoiding confrontation, it becomes a powerful tool for social transformation.

Why Active Ahiṃsā Works

This moral distinction becomes apparent to observers over time. The more people recognize that nonviolent activists are working for collective wellbeing rather than narrow self-interest, the stronger the movement becomes. Nonviolent activism is, at its core, an exercise in solidarity with all people. The more who participate, the more successful it becomes.

Nonviolence, the procedural kind, is destructive.

Resetting the Moral Order

‘They say, “means are, after all, means.” I would say, “means are, after all, everything.” As the means so the end…’

—Gandhi (1959). Sarvodaya. India of My Dreams. Ahmedabad,, Navajivan Pub. House: 65-68.~~~~~